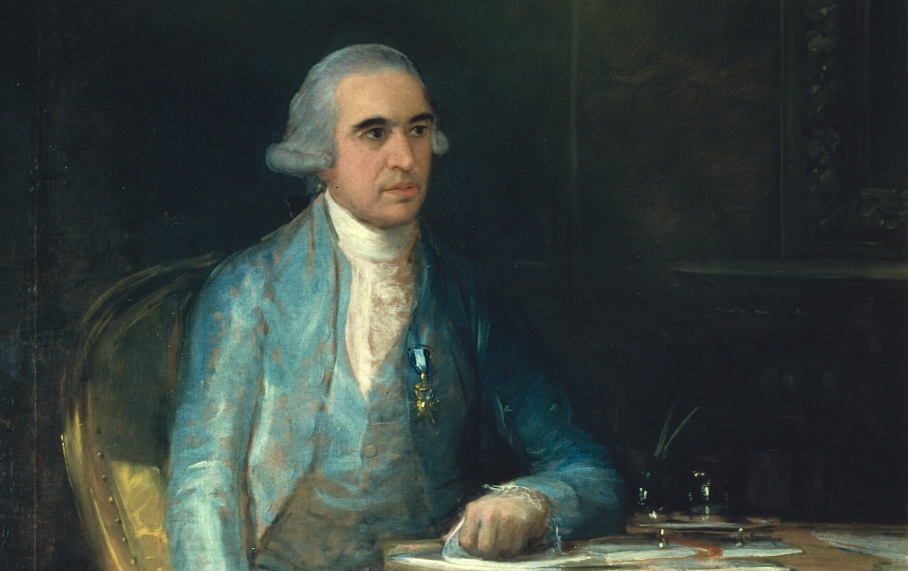

Image: Saavedra as painted by Goya in 1798 while Minister of Finance. He is wearing the Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos III conferred on him by Carlos III as a result of his mission to Havana in 1781 during the American Revolutionary War.

Francisco de Saavedra played a key role in the combined American and French victory over the British at the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781, a victory that led to the British abandoning the war in North America.

Saavedra had been appointed a Royal Commissioner and sent by the Spanish crown to Havana where he arrived in January of 1781. His mission was to ensure that Spain’s goals were achieved as the Havana War Council (the Junta de Generales) was divided over its priorities in the war. On arrival, he set about unifying the Junta which was not supporting Bernardo de Gálvez’s expedition to take British held Pensacola in West Florida. The objective here was to evict the British from the Gulf of Mexico and therefore eliminate any threat to Spanish-held New Orleans, which was then the gateway to the Mississippi and the American rear-guard.

In April 1781, Saavedra oversaw the arrival of a massive reinforcement to Gálvez’s forces outside Pensacola, which soon led to the capitulation of the British occupiers. Returning briefly to Havana, he soon sailed for Cap François (today Cap Haitien, Haiti) aboard a French naval squadron whose commander, Chevalier de Monteil, he had befriended. Saavedra’s mission was to coordinate French and Spanish war plans with a large war fleet, which was arriving from France commanded by Lt. General de Grasse.

After de Grasse’s arrival on the 16th of July, Saavedra quickly produced a campaign plan, and since the summer hurricane season in the Caribbean was about to start, Saavedra backed the French plan to sail to North America to help the combined American and French armies of generals Washington and Rochambeau defeat the British either at New York or in Virginia. De Grasse chose Virginia as he knew his large fleet could not enter New York harbor due to the sand bars at Sandy Hook, and he took his entire fleet of 28 ships and 3,300 troops to reinforce Washington and Rochambeau. De Grasse was able to do this because Saavedra committed to providing Spanish naval protection to Cap François which would be left relatively undefended.

However, a final and almost insurmountable stumbling block for de Grasse was that he had no money either to provision his fleet or to meet Rochambeau’s desperate request for 200,000 Spanish silver dollars with which to fund the army in North America. When the French in Cap François refused to lend de Grasse any money, he immediately turned to Saavedra for help.

Saavedra had already provided $100,000 to refurbish the French fleet when de Grasse approached him with a request for a further $500,000 for his fleet and for the army in North America. However, seeing the predicament de Grasse was in, Saavedra offered to sail for Havana where he raised the $500,000 in a day. This money was immediately transferred to the French fleet as it sailed past Havana northwards to Chesapeake Bay.

Washington had been so short on cash in North America in early 1781 that he had suffered two mutinies among his troops, and he had had to execute the ring leaders to help restore discipline. So it was probably not surprising that, during the march south from New York to intercept the British at Yorktown, some Continental Army troops mutinied in Philadelphia. The French army’s treasury, knowing that more silver was on its way with de Grasse, was able to lend Washington the necessary money to pay his soldiers and get them on the move again.

By the time Washington and Rochambeau’s armies arrived at Yorktown, the British had already been trapped at Yorktown by American troops under the Marquis de Lafayette and French troops from de Grasse’s fleet under the Marquis de Saint Simon. De Grasse had also defeated a British fleet that had tried to make a last-ditch effort to rescue the British army at Yorktown in what is known as the Battle of the Chesapeake.

When Washington and Rochambeau visited de Grasse aboard his ship, the Ville-de Paris, they returned to land with the Spanish silver raised by Saavedra in Havana. Claude Blanchard the French army’s quarter master, to whom the money was entrusted, wrote that the floor of his house collapsed with the weight of this silver which would have weighed around 3.5 tons. He wrote that, “During the night, while more slumped than dozy, the floor of the room adjoining mine collapsed with a crash. This accident came from the silver which I had placed there. It was on the ground floor and underneath there was, happily, a shallow basement. The floor was too weak and had not been able to hold the weight of these 800,000 livres in silver. My servant, who slept in this room, slid down a beam but did not suffer any injury…”.

The money would enable the allies to amply provision their armies and help defeat the British who would surrender on October 19th, 1781. This would be recognized by the French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, in a letter to his ambassador in Madrid in which he requested that thanks be given to the Spanish King, Carlos III. Vergennes would add that if the harmony that the agreement created between de Grasse and Saavedra could be sustained, “we can promise ourselves some happy results from the combination of our forces…following M. de Grasse’s account it is not possible to have put greater amenity, goodwill and disposition to the agreement than M. de Saavedra showed…”.

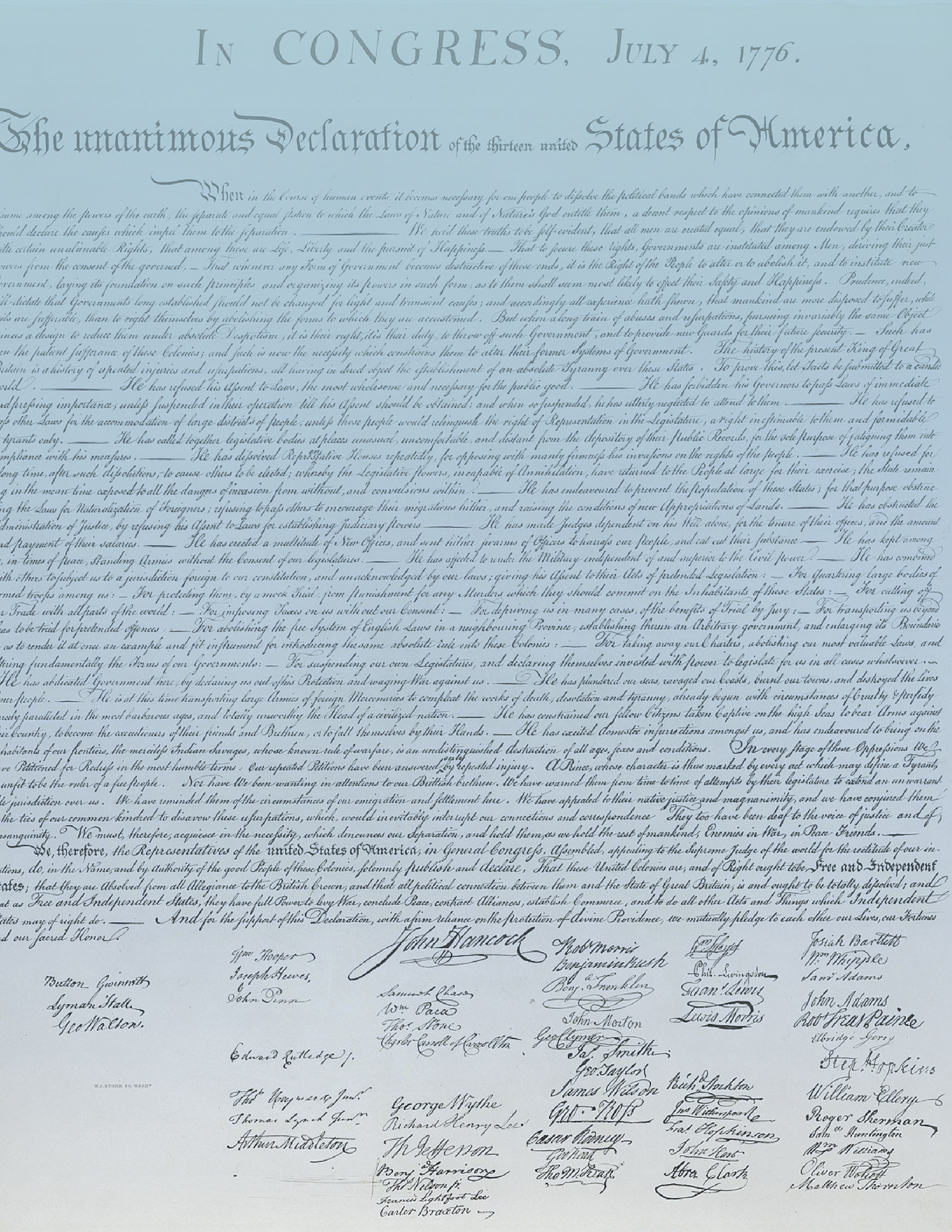

These “happy results” would include the independence of the United States, which would be later confirmed in the Treaty of Versailles signed in September 1783.

James Giesler completed a Masters degree in American Studies (Estudios Americanos) at the University of Seville in 2016. His forthcoming book “Francisco de Saavedra’s American Revolutionary War, The Spanish contribution to the Battle of Yorktown” is based on his dissertation for his Masters degree. He completed a bachelors degree in Law at the University of Exeter (UK) in 1986 and has had a career in finance and real estate.