Bananas are the most consumed fruit in the world. In the United States, we peel them without much thought to how they reached our supermarkets from the tropics. In Latin America, where the United States’ bananas are grown, the fruit isn’t taken for granted.

While the banana tree is originally from Asia, the plant was brought to the Americas by Spanish colonists. Eventually, the fruit would come to shape modern Latin American history. The pressures of international banana trade and vast plantations have led to the exploitation of the land and people.

Unsurprisingly, the banana has much more serious overtones in Latin American art than in art in the United States.

In 1968, Andy Warhol silk-screened a banana instead of a Campbell soup can. The piece “Peel and See” plays with sexual innuendo in an everyday dietary staple. In 2017, the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan commented on the artworld by duct-taping a ripe banana to the wall at Art Basel in Miami. The installation called Comedian recalls the slap-stick gag of slipping on a banana peel.

In Latin America, banana art takes on bigger questions. “Almost every issue of contemporary Latin America can be told through the history of bananas,“ Blanca Serrano, Project Director at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), explained.

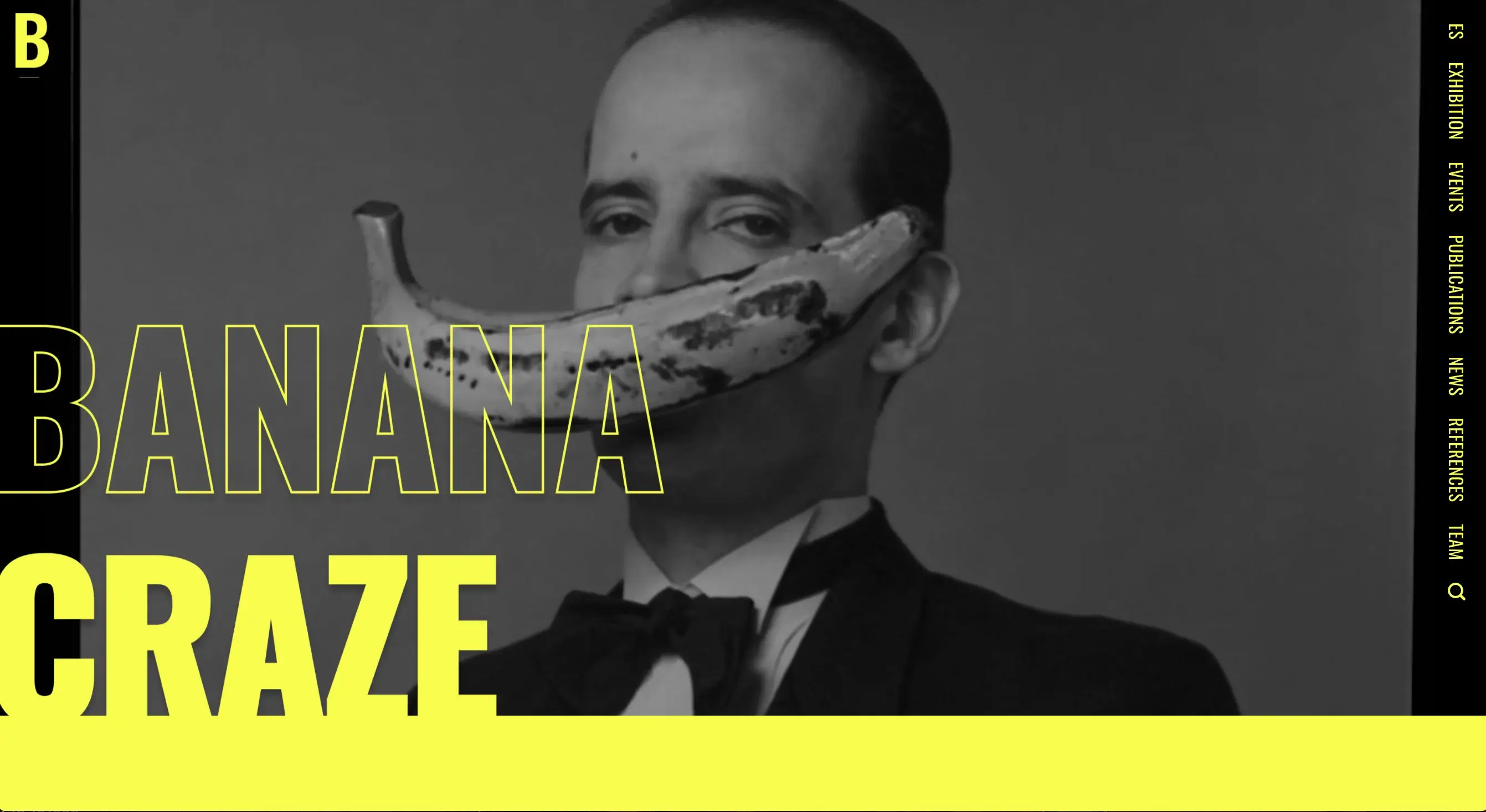

Serrano and her collaborator Juanita Solano, Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History at Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, have developed an omnibus project focusing on the banana in contemporary Latin American art. The project La Fiebre del Banano – Banana Craze consists of a vast virtual art exhibition, an online archive, and an ongoing research project. The art is divided across three virtual galleries: violences, ecosystems, and identities.

The seed of the project comes from Serrano and Solano’s 2017 installation at the Cuchifritos Gallery in New York, Bitter Bites: Tracing the Fruit Market in the Global South. It was then the two curators realized how common the banana was in contemporary Latino and Latin American art. However, La Fiebre del Banano – Banana Craze is truly a product of the pandemic. For the past two years, working with students from La Universidad de Los Andes, Serrano and Solano have created a detailed virtual gallery of almost 100 artworks from artists across North and South America. Funding for the project comes from the university, and English translations were contributed by the British-based non-profit organization Banana Link.

Caballería (Cavalry), Cuban Raúl Corrales

The exhibition is a rare case where the online format adds to the visitor’s experience. Serrano and Solano allow the viewer to explore the artwork organized by theme, a clickable map, and an interactive timeline. Chronologically, the first piece is a 1960 photo by the Cuban Raúl Corrales. The photo, called Cavalry (Caballería), captures revolutionaries on horseback waving Cuban Flags as they reenact the expropriation of a plantation owned by The United Fruit Company during the 1959 uprising.

That the curators use this image as their starting point makes clear that contemporary Latin American artists use the banana not just as a symbol but as an actual means to empowerment. This becomes clear in references to the 1928 massacre of banana workers by the United Fruit Company in Colombia, and the 1954 coup of Guatemala, also orchestrated by the United States-based corporation.

The exhibition isn’t just a history of political violence and labor abuses. It also contemplates the future. The Brazilian artist Daniela Serruya Kohn proposes recycling banana skins into paper or preserves. Serruya Kohn’s mixed media piece appears in the Ecosystems gallery. This section reflects on the monoculture of bananas. “Not diversifying the economy and the diet of local people,” Serrano explained, causes a litany of problems. The artwork reflects on questions of water use, health issues from pesticides, and deforestation.

Chiquita, María José Argenzio

Looking through the galleries, it is striking to find so many common themes in the art that spans 60 years and originates in 20 countries. Many artists directly comment on the major United States banana companies. María José Argenzio, an artist from Latin America’s largest banana producer Ecuador, in her piece Chiquita, presents a gold-leafed banana sculpture drawing a comparison between the banana industry and the extraction of gold in the colonial era. Mexican artist Minerva Cuevas alters the Del Monte Fresh Produce logo to read: “Del Montte criminal, Guatemala struggles for land.” A reference to José Efraín Ríos Montt, a 1980s Guatemalan military government leader charged with crimes against humanity. While in the Identities gallery, Puerto Rican artist ADÁL reimagines the Chiquita logo, a cartoon version of the mid-20th-century pop star Carmen Miranda. The artist inverts the comic logo that represents the stereotyping of Latin Americans as exotic and sensual.

In some cases, the artists make references to each other’s works, but for the most part, it appears that each artist has independently discovered the banana as a powerful symbol. In this sense, Serrano and Solano in La Fiebre del Banano – Banana Craze have revealed a political iconography that spans the continent.

Andrew Silverstein writes about New York and is co-Founder of Streetwise New York Tours.