How Spain’s Contribution to the American Revolutionary War Left American History Books

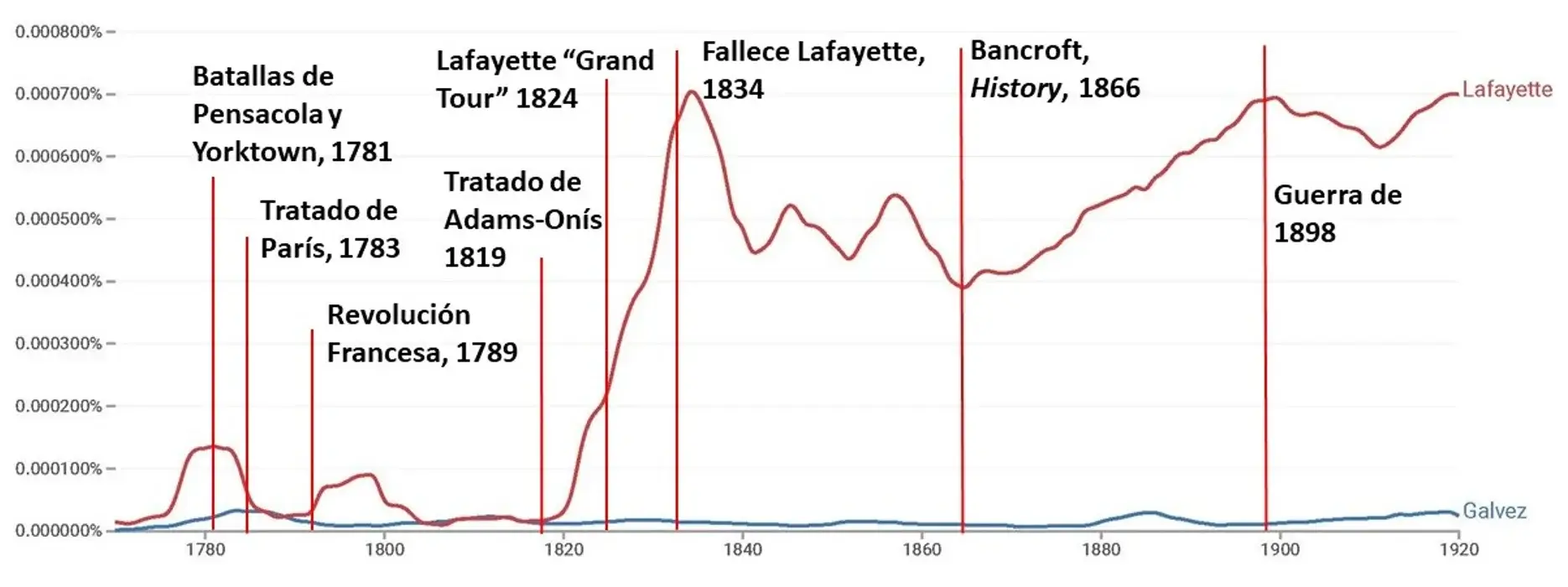

This chart shows the frequency of the names “Lafayette” and “Gálvez” used in English-language literature (courtesy of Google Ngram) from 1780 to 1920, sometimes referred to as “the long nineteenth century”.

“Lafayette” and “Gálvez” are really proxies for the recognition of (respectively) France and Spain in the War of American Independence, as both men are by far the most emblematic figures for their respective nations.

The chart shows that during the war, Lafayette (and therefore France) was more recognized than was Gálvez (and Spain); not surprising since France fought side-by-side with the Americans, while Spain was occupied in more distant theaters.

What is most interesting is that after the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the war and for over forty years (until 1824), the names of both Lafayette and Gálvez receive approximately equal recognition for the American Revolution. The bump for Lafayette during the French Revolution reflects mostly his role in the National Assembly, in exile and as author of the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

In other words, for a long period of time after the War of Independence, histories of the war recognized both France and Spain as participants alongside the United States.

The recognition of Lafayette (and therefore France) becomes significantly elevated with his tour of America from 1824-1825, which cemented his reputation as “the hero of two worlds”, and was enshrined with his death in 1834. George Bancroft’s History of the United States (1864), by far the most influential set of history books for a hundred years, further glorified Lafayette’s role.

But Bancroft was an unabashed crusader for Manifest Destiny, the belief that America should extend its domain across the hemisphere, and the Spanish legacy was clearly an anathema to that. His History deprecated and dismissed the Spanish role in American independence. Following Bancroft’s lead, both Gálvez and Spain disappeared from American histories of the Revolution for over a century.

The twentieth century saw a resurgence in the recognition of Spain and Gálvez, though at first very slowly. John Caughey’s 1934 book Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana was the first English-language biography, and Gálvez’s name became even more prominent in military histories written during World War II. The American bicentennial of 1776, during which an equestrian statue of Gálvez was dedicated in Washington, DC by King Juan Carlos I, saw a small bump in recognition.

But it was not until the 21st century that Spain and Gálvez began to receive their due. The publication of Thomas Chávez’s magisterial Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift in 2002, followed by the unflagging efforts of Teresa Valcarce and others in 2014 to unveil a portrait of Gálvez, along with a parallel effort to accord him honorary US citizenship the same year, as well as the recent biography Bernardo de Gálvez: Spanish Hero of the American Revolution by Gonzalo M. Quintero Saravia, all have resulted in a sudden surge of recognition for Spain’s crucial role at the birth of the United States. The efforts of the Spanish Embassy, Queen Sofia Spanish Institute, the Society of the Cincinnati and many others continue to drive this long-overdue acknowledgement of the shared histories of the two nations.